The State of Diversity in Life Sciences

The State of Diversity in Life Sciences

11 Min. Read

The upheavals of the recent past have not been limited to disrupted supply chains and stay-at-home orders. The United States in particular has been engaged in a reckoning with its changing demographics and the history of gender- and ethnic-based exclusion. The 2020 census showed the White population of the United States is under 60% for the first time ever, and the population under 18 is majority non-White. The life sciences industry is addressing this demographic shift, but more can—and should—be done.

The Importance of DEI

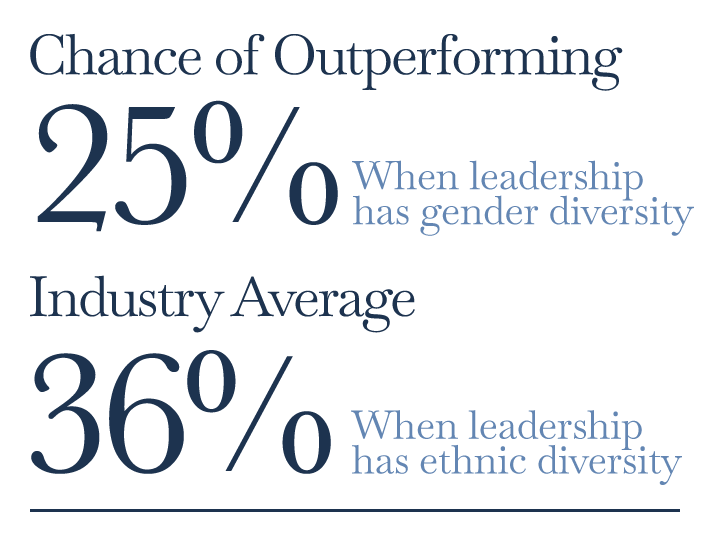

Diversity of background leads to diversity of thought and perspective. This alone might be enough to assure that a desire for representative diversity exists at a company. Recent efforts to quantify how diversity affects the profitability of a company have shown a strong correlation between ethnic and gender diversity and greater profitability in a company. McKinsey has run three surveys dating back to 2014 on this topic and their most recent data show that when leadership is diverse by gender, there is a 25% greater chance of out-performing industry average EBIT. In the case of ethnic diversity that chance is 36%.

The distance between correlation and causation here is critically important. Robin Ely and David Thomas, writing in the Harvard Business Review offer the following caution of overstating the relationship between diversity and profitability. “Research suggests that when company diversity statements emphasize the economic payoffs, people from underrepresented groups start questioning whether the organization is a place where they really belong, which reduces their interest in joining it. In addition, when diversity initiatives promise financial gains but fail to deliver, people are likely to withdraw their support for them.”

Ely and Thomas’s cautions about the dollars-and-sense business case has great merit, but they are not simply naysayers. They do offer a constructive paradigm with which companies can engage. It is not a quick or an easy solution; rather, it entails doing hard work and fundamentally reshaping company cultures. They recommend working within a learning paradigm which they acknowledge is likely a shift for most leaders and managers. There are four key steps identified here: building trust, actively working against discrimination and subordination, embracing a wide range of styles and voices, and making cultural differences a resource for learning. The authors are quite clear that this is not quick work, nor is it especially easy work. As we have noted elsewhere, however, it is highly necessary work.

The State of Diversity in Life Sciences

The Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) published their second annual survey of diversity in biotech companies and leadership in June 2021. The survey was developed in conjunction with Coqual as a follow-up to their initial benchmark study of 2019. The study shows some promising trends; however, it is admittedly a small sample size of 100 BIO member companies. While appropriate cautions regarding extrapolation from small sample sizes should be kept in mind, this study is worth examination as it relates to the state of diversity—and efforts to increase diversity—within the biotech industry.

The greatest hurdle to overcome in examining diversity in any industry is the fact that not every company or organization tracks demographics in the same manner or with the same rigor. Numbers on diversity in sexual orientation or gender identity are hard to come by and asking for those reports can appear incredibly intrusive. Diversity in physical ability is similarly under-reported if it is reported at all. The most reliable statistics available deal with ethnicity and binary gender, although BIO does note that they are attempting to gather a broader spectrum of diversity statistics.

Of the companies surveyed, BIO found that the vast majority either stayed at the same size or grew. Only 3% saw contraction between 2019 and 2020. Of the 26% of companies that grew, some increase in diversity could be attributed to that growth. The 71% that stayed the same represent a more promising possibility: that non-diverse employees who left may have been replaced by diverse employees.

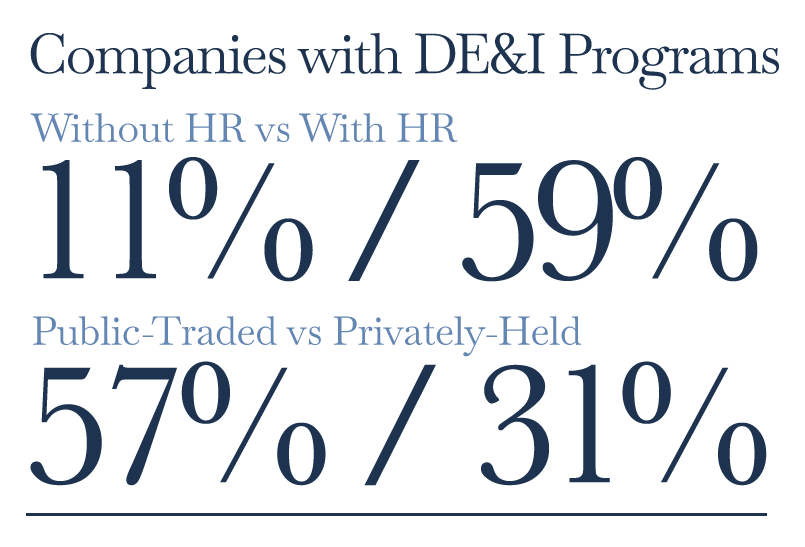

DEI programming generally lives in the human resources department. It should not be surprising that companies with dedicated HR staff were more likely to have some kind of DEI programming than those companies that do not have dedicated HR staff. The difference is quite stark: 59% of firms with HR staff have some kind of DEI programming, while only 11% without HR staff do. Additionally, publicly-traded companies outpaced privately-held ones at a rate of 57% to 31%. Perhaps most encouraging is the increase in DEI programming participation which rose by nearly 165% overall, from only 17% of respondents in 2019 to 45% in 2020.

Looking first to diversity along the male/female gender binary, we can see that while the total workforce is mildly tilted away from census representation at 53% male/47% female, the composition of the executive team is worse at a 69% male/31% female split. In the CEO role, things get worse still with men outnumbering women at a rate of 76% to 23% with 1% not reporting CEO gender.

The trends, however, do show some improvement. Among total employees, 36% reported moderate or significant increases in diversity. Only 6% reported a moderate decrease. In the executive ranks, women’s representation improved by a moderate to significant amount—defined as 5%-15% for “moderate” and over 15% for “significant”—in one third of companies surveyed.

Gender is of course only one dimension of diversity. When looking into ethnic diversity, the BIO survey reveals that White employees are overrepresented compared to census levels (65% in the industry/57.8% in the 2020 census). The executive ranks surveyed are 78% White overall and 74% White in the CEO role. When examining the trends at the executive level, 20% saw a decrease in ethnic diversity and only 14% saw an increase.

Although the headcounts are not encouraging, companies are paying attention to the issue of under-representation. The survey shows positive year-over-year growth on every question regarding a company’s stated commitment to DEI efforts. Accountability, however, lags behind the public statements. 68% of respondents indicated that DEI efforts are led by employees and do not have any formal accountability structures. Only 39% claim that leadership teams have specific DEI goals, and merely 20% state that DEI metrics have any impact on performance evaluations or compensation for those leaders.

All of this will take work to correct. 95% of surveyed organizations have made the recruitment and hiring of diverse talent a priority. Fully 87% of that recruitment, however, comes from current employee referrals. While such referrals are of course helpful in building an inclusive culture, this runs the risk of relying on one’s diverse employees to fix the diversity problem for the company instead of adopting policies and practices that would fix the problem for the diverse employees.

The ZRG DEI Benchmark Study

ZRG recently conducted a benchmark study of DEI efforts in companies across multiple industries. These companies included media, tech, industrial, consumer, and—importantly for the present discussion—life sciences and healthcare organizations, which comprised the largest plurality of any industry in the study. This study was conducted through a series of interviews with company executives who had oversight of DEI programming: Chief DEI Officers, Chief Talent Officers, and Chief Human Resources Officers.

We were particularly interested to find out both to whom the person or people in charge of DEI efforts would report and, where appropriate, what title was used by a c-suite leader in charge of DEI at a company. We found that the DEI function in life sciences and healthcare mostly reports to the CHRO at a rate of 65%. Interestingly, however, 25% of surveyed life sciences and healthcare firms have the DEI function report directly to the CEO. This was exceeded in our study only by finance/fintech/insurance, where 40% of companies have the DEI function report to the CEO. It is a mark of how seriously life sciences and healthcare are taking DEI issues to have this short of a path to the company leader.

Life sciences and healthcare companies were the most likely to have a Chief DEI Officer as well. Here we saw nearly 90% of firms with that role, while slightly more than 10% have a CHRO in charge of DEI efforts. Tech and telecom firms were the next most likely to have a Chief DEI Officer, while the title appeared the least in the financial and insurance sector.

Apart from reporting structures, our study also examines the public facing statements and policies made about DEI. Fully 97% of companies in our study consider DEI a strategic priority. 81% of studied companies have added DEI language to their Mission, Vision, and Values statements, and an equal percentage have a formal DEI office or program. Similarly, 81% of our study are speaking publicly about DEI topics. These numbers are encouraging in the main.

The fact that while 91% of companies have DEI goals only 59% publish them is perhaps more worrisome. The concern for transparency is present in both the BIO study and in Ely and Thomas’s work discussed above. For companies to truly embrace DEI and do the difficult work Ely and Thomas suggest is necessary, transparency and public accountability must be part of the program. Efforts that are only addressed in a purely internal manner will have less reach into the talent pool; if nobody knows how a company is doing on DEI, it is less likely that they will attract the best diverse talent in order to reach their diversity goals.

Leadership buy-in is necessary to ensure that DEI programming is properly resourced and becomes a durable part of company culture. We found that 56% of executive leadership teams have DEI as part of their performance objectives. While it is encouraging that this is a majority of companies, tying DEI goals to performance among executive leadership should be an easy way to ensure top-level buy-in. It is therefore somewhat discouraging that this percentage is not higher than a small majority.

Our study shows that affinity groups—groups in which under-represented employees can create a supportive environment for their concerns—are largely run by volunteer employees. Most companies studied have between one and nine affinity groups, although that is a small plurality of 44% compared to 40% with more than ten and 16% with none. Within the companies that have affinity groups, 40% are run by volunteers, 16% by employees noted as having high potential for leadership, and 28% by a mix of those two groups. This gives us a sense of the “bottom-up” buy-in as compared to the “top-down” approach above.

Fixing the crisis of diverse talent in any industry will require close review of company HR processes. We found that the vast majority of companies—over 90%—have undertaken a review of their talent acquisition process. This is done by reviewing language in job descriptions, on a career website, ensuring diverse candidate slates and interview panels, and making reasonable accommodations for candidates with disabilities. Nearly 80% have reviewed compensation practices, including both cash compensation and benefits, to eliminate unconscious or legacy bias. Only half, however, have put leadership competencies and leadership training programs under the same scrutiny.

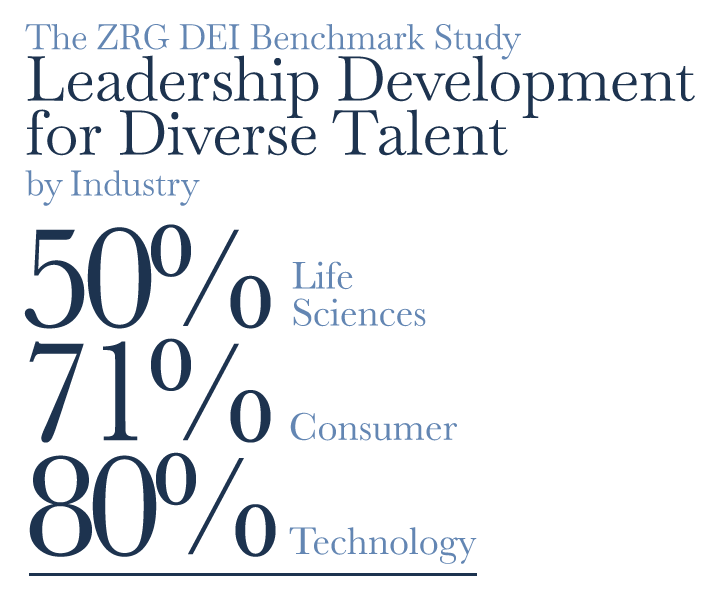

When it comes to leadership development programs, we found that life sciences and healthcare firms lag behind both the retail/consumer sector and the tech/telecom sector. 75% of life sciences and healthcare firms have leadership development for high potential employees while the rate in consumer and tech is 100% and 80% respectively. Leadership development for diverse high potential employees also lags in this sector. Half of the life sciences and healthcare companies we studied have such programs, while 71% of consumer firms and 80% of tech firms do. Among the industry verticals in our study, this puts life sciences and healthcare precisely in the middle of the road. While it may be costly in terms of time and budget to develop internal development programs, external programs exist and can be supported more readily.

Employees are recognized as having high leadership potential in a variety of ways. The most common nomination mechanism for inclusion in a leadership development program is via formal talent review. 69% of nominees are selected in this fashion, while 31% are selected by manager nomination. Executive sponsorship is sometimes offered during or after a leadership development program; 27% of companies offer this level of access and buy-in. Mentorship is offered more frequently, at a rate of 46%.

The success of leadership development programs can be measured in a variety of ways. For some firms, this means tracking promotions by rate and velocity among the target demographic. For some, this means measuring retention of diverse employees across a variable timeframe. Others look to an overall retention rate among diverse groups, reflecting both gender and ethnic diversity. Some firms measure the success of their leadership development programs by comparison to a control group of employees who were not part of the program.

Building a Pipeline for Diverse Talent

Looking to both the BIO and ZRG studies of diversity in life sciences, it is clear that continuing at the current rate of change will not result in a representative and diverse industry in a short period of time. As we have noted previously regarding corporate board service, one of the best ways to do this is to begin building a pipeline for diverse talent. Companies simply cannot wait for talented individuals to show up on their doorstep, nor can a lack of progress toward diversity goals be dismissed as pursuit of a meritocratic hiring philosophy. Work toward this goal can certainly start with the employee corps, but they need to know that there is a commitment from the c-suite and the board to truly transform the company. Changing from the bottom up is certainly a way to achieve diversity and belonging, but there needs to be top-down commitment at a more than verbal level. Diversity and belonging can be competitive advantages, but their attainment will require work and commitment. Building a pipeline and showing employees a clear path for advancement will start any company on this journey.