Place and P.A.C.E. in Healthcare

8 Min. Read

The explosion in telemedicine throughout the COVID pandemic has illustrated the importance of place in the provision of healthcare. Healthcare doesn’t just happen in the doctor’s office any longer. Now patients are likely to seek care in a walk-in urgent care clinic that may or may not be affiliated with a larger hospital or hospital system. The pandemic has also highlighted certain inequalities in the provision of healthcare in the United States in particular. We are living in a moment in which ESG concerns—Environmental, Social, and Governance—are top-of-mind to leaders across all industries, hospitals and healthcare systems very much included.

Social Determinants of Health

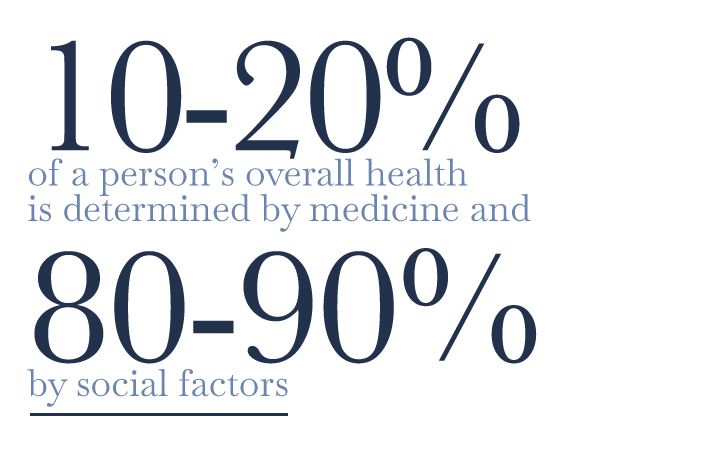

Beyond a strict focus on the physical and physiological function of the body, medicine is now considering “social determinants of health”. This refers to the environmental, social, and economic conditions that can impact a person’s living quality. The CDC’s Healthy People 2030 program uses a place-based framework to outline five key areas of these social determinants: healthcare access and quality; education access and quality; social and community context; economic stability; and neighborhood and built environment. Health could be judged solely through medical analysis but, according to many medical sources, healthcare treatment only makes up 10-20% of a person’s health status. The remaining 80-90% of health status is directly impacted by the social determinants above.

COVID has been a startling case-in-point proof of the importance of using a social lens to understand health disparities. A person’s response to COVID is not just related to their healthcare provider. The initial global healthcare response to COVID was to implement non-pharmaceutical intervention, which meant trying to limit person-to-person contact to minimize the spread. If healthcare was the only factor in this situation, it would be understandable for people to stay home to keep themselves and others safe. Unfortunately, because of the other social factors, not everyone is able to stay home. Some people are unable to work remotely, either because they don’t have the resources at home to do so, or because their jobs won’t allow them to. A person being forced to go into work could also impact a family who relied on school for childcare. School may have been made remote, but that doesn’t mean the child’s family was also able to stay home to watch them. These issues have been documented primarily in BIPOC communities, and have led to unemployment, food insecurity, and a decrease in mental health.

Deirdre Allison, Managing Director in the Healthcare practice at ZRG partners remarked “Rapid strides have been made in unlocking the business value of ESG in recent years, driven by economic and social impacts facing the world today.” She continued, “Specific ESG issues that a company faces vary wildly by industry and company maturity, and there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution; many of our healthcare clients are finding that they must prove their credentials with growing frequency.” In all cases, directors and CEOs will play a big role in guiding management to allocate the appropriate resources and attention to ESG. Forward-looking companies value being a front runner on ESG issues because they see the connection to the company’s long-term success.

Allison mentioned “I had a healthcare CEO recently tell me that ESG is ‘a table takes issue, an enterprise-wide initiative, many of us are hiring a Chief Sustainability and Inclusion Officer. We believe that there will be monetary implications of not addressing or dealing with these issues, this is a practical model that implores healthcare organizations to effect change, change the mind-set and move towards inclusion. Companies have a social and moral conscience about ESG, and sadly these issues adversely affect education and healthcare parity.’”

On top of these issues, there is a huge lack of reliable, available, and thorough data on healthcare resources and community health issues. There is not a framework that accurately shows the statistical reality of what certain people are going through. This breeds distrust and can cause already marginalized groups to be underrepresented.

Place in Healthcare

All three keystones of ESG come into play in healthcare real estate. Environmental and social concerns are, in fact, very difficult to tease apart in this context. Where a patient lives can have an immense impact on their health, from the kind of care available to the quality of care received. It would not be an overstatement to suggest that a patient’s lived environment has as much bearing on her or his health as diet or heredity.

While “food deserts”—areas in which fresh, healthy, food is unavailable—have been a point of increasing concern, we must also attend to the existence of various types of “health care deserts.” A September study by GoodRx Research, reported in HIT Consultant, examined the state of healthcare desertification in the United States. They defined a healthcare desert as a geographical area in which people lacked sufficient access to healthcare in six key areas: pharmacies, primary care providers, hospitals, hospital beds, trauma centers, and low-cost health centers. The study found that 8.4 million people in the United States live in a county with desert-level deficiency in at least four of these six categories.

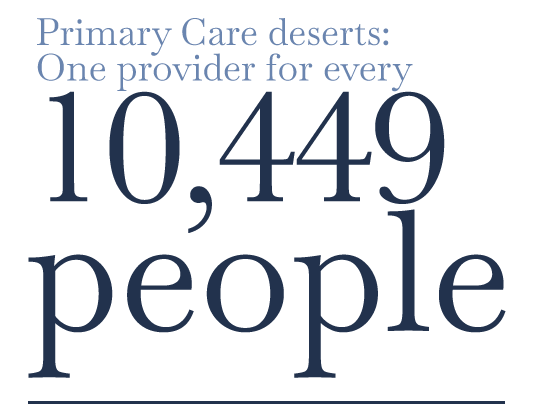

GoodRx Research found that over 40% of all counties in the United States are a pharmacy desert in which residents must drive over 15 minutes to reach the nearest pharmacy. Of course, one must first visit a physician to obtain a prescription. Sadly, primary care access was not much better. They found that “on average, healthcare provider deserts have 1 full-time primary care provider for every 10,449 people — a potential patient caseload over three times the recommended level.”

Worse still than primary care access, roughly 47% of all counties in the United States—with a population of approximately 80 million—are defined as deserts for hospital beds. Simply put, there are not enough beds in those hospitals to accommodate the population if need arose. The COVID-19 pandemic has put additional strain on these areas, in some cases resulting in rationing and triage of the available space.

The correlation between low income and lack of access to healthcare is strong. The report finds that “…healthcare deserts are more likely to occur where residents have lower-incomes, less insurance coverage, and more limited internet access. States with a higher rate of population lacking internet access according to the census tend to have more healthcare deserts.” Unsurprisingly, rural and low-income areas are most directly affected by this dynamic.

If we know where the need for healthcare providers is, how are we still struggling to meet the need for care, in terms of both primary care and hospital beds? What might seem initially like a tragic imbalance of supply and demand has a capital and real estate dimension overlaid.

A have/have-not anecdote applies to health systems and hospitals throughout the USA. There are two different waves surrounding healthcare real estate: one involves great expansion—including several billion-dollar state-of-the-art new research and care facilities—while the other is the closure and shrinking of care facilities in already underserved geographies. Solutions for both scenarios revolve around cost and access to capital. “Like all real estate investments, healthcare real estate projects are underwritten and scrutinized by investment companies,” says Kevin Jones, Managing Director and Real Estate Practice Leader at ZRG. “Every project is evaluated on cap rates, yield, and ROI, which don’t necessarily align with community needs, meaning it will be difficult to find answers within a traditional real estate capital stack.”

PACE in Healthcare

The tie-up of capital in existing facilities and payroll obligations need not, however, mean that hospitals and healthcare systems are unable to respond to ESG needs. Aside from more traditional cost-cutting or fundraising measures, there are newer and more creative ways to address capital needs. One of these is Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy financing (C-PACE).

The tie-up of capital in existing facilities and payroll obligations need not, however, mean that hospitals and healthcare systems are unable to respond to ESG needs. Aside from more traditional cost-cutting or fundraising measures, there are newer and more creative ways to address capital needs. One of these is Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy financing (C-PACE).

“C-PACE funding can be an attractive capital option for healthcare providers looking to complement their existing capital structure, while both reducing their occupancy costs and making their real estate more efficient and sustainable,” notes Joe Euphrat, Managing Principal with GreenRock. “Our C-PACE funding solutions can be utilized by owners and users of healthcare real estate for new construction, expansion projects, resiliency, and ongoing capital expenditures. In addition, there are no financial covenants with GreenRock’s financing.”

C-PACE funding is not only used to make a business “greener”. Hospitals along the Gulf Coast can use this funding for hurricane strengthening, as Euphrat alluded to. California businesses can use it to protect against wildfires. “In terms of climate change, C-PACE funding can allow companies to respond to a changed climate,” says Chris Robbins, Managing Principal at GreenRock. NASA currently estimates that sea levels will rise by 1-8 feet by 2100, hurricane season will be longer and more violent, and droughts that fuel wildfires will increase. Healthcare providers need to be able to respond to the physical needs that result from these changes.

Beyond just climate issues—the “E” of ESG—using C-PACE funding to reduce capital expenditures can help healthcare providers address the issue of healthcare desertification. With more funds available, expansion becomes easier, whether that is expansion of the workforce or physical expansion into under-served areas. C-PACE funding can, in other words, help healthcare providers address the issue of healthcare desertification. Simply building more hospitals and urgent care centers will not solve the healthcare gap in one fell swoop. It is, however, a positive step toward addressing the concerns raised in the investigation of the social determinants of health. Increasing access to healthcare facilities and providers can—indeed should—have a net positive effect on the overall health of the population. While there is no magic bullet to solve this complex issue, the use of C-PACE funding to free up capital provides a creative solution to at least part of the problem.